No Palpation without Instrumentation!

- Valeria Krivelevich

- Apr 13, 2021

- 4 min read

Updated: Mar 26, 2025

I wrote this several years ago and recently came across it. The content still rings true today. I hope you like it...

We cannot treat that which we cannot see.

Recall the last time that you went to your friendly neighborhood Phrenologist. He or she undoubtedly observed and palpated your cranium for important landmarks that held a key to the deep inner workings of your mind and made recommendations based on his or her findings. Oh, you haven’t been to a phrenologist? What is a phrenologist you ask? Well, that is likely because phrenology, “the detailed study of the shape and size of the cranium as a supposed indication of character and mental abilities” most popular in the 1810’s to the 1840’s, has been debunked as a pseudoscience. You see people are not equipped with X-ray vision, and the acts of observing and palpating have largely given way to advances in modern technology such as X-ray, Fluoroscopy, CAT Scan, MRI and Endoscopy.

So why do some Speech-Language Pathologists who work with patients with dysphagia continue to utilize these methods as a primary diagnostic tool? Just like it is not possible to determine the internal workings of one’s mind by observing and palpating his skull, we cannot determine the internal workings of the very intricate swallowing mechanism by observing and palpating the throat.

Simply stated: We cannot treat that which we cannot see.

The bedside dysphagia evaluation is a powerful screening tool. It can give us much information regarding our patients’ cognitive status, their ability to follow commands, their level of awareness of the feeding situation and whether they are independent or dependent for feeding. It also informs us about their dentition, the strength and range of motion of their oral structures and which cranial nerves may be leading to deficits in strength, range of motion, and tone of those structures. Likewise, we can assess their ability to orally handle their own secretions, their vocal quality, their willingness and ability to accept food into the oral cavity and their ability to contain that food within the oral cavity with their lips. Visible deficits such as the complete absence of oral preparation, oral pocketing, anterior leakage and oral residue after a swallow can paint an accurate diagnostic picture. However, the subtle movements within a closed oral cavity during the act of oral preparation and transport of the bolus simply can not be seen. As a result, we are left to make an educated guess about such things as anterior/posterior transport, posterior oral containment of the bolus, velar to palate contact and other pertinent details of the oral phase of the swallow not visible to the naked eye.

And what about the pharyngeal stage? According to the American Speech and Hearing Association (ASHA), “a non-instrumental assessment may provide sufficient information for a clinician to diagnose oral dysphagia; however, aspiration and other physiologic problems in the pharyngeal phase can be directly observed only via instrumental assessments.”

Speech Pathologists are frequently taught to use digital palpation of the thyroid notch to gauge laryngeal elevation and excursion during the swallow. But how accurate is this? A literature review conducted on hyoid and/or laryngeal displacement during swallowing in healthy populations by Sonja Molfenter PhD and Catriona Steele PhD revealed that “the smallest mean superior hyoid displacement comes from the Ishida and colleagues study [21] at 5.8 mm, while the largest is 25.0 mm from the Logemann study.” That is a difference of 19.2 mm! Without realizing it, some Speech Pathologists may diagnose a patient with perceived reduced hyolaryngeal elevation as having dysphagia when in fact this may be the patient’s norm.

Even if we feel laryngeal elevation occur, we have no information regarding arytenoid adduction, epiglottic deflection, closure of the vocal folds, pharyngeal squeeze, and relaxation of the upper esophageal sphincter; all exceptionally important steps in the swallow mechanism that can significantly impact an individual’s ability to consume a meal safely.

Then there is the question of laryngeal penetration or aspiration and pharyngeal residue. Aspiration, the entrance of food or liquid below the level of the vocal folds, into the trachea, which is the entryway toward the lungs, is related to increased morbidity and mortality. Coughing, throat clearing and changes in vocal quality during or after a swallow or meal are considered to be some of the signs related to an event of aspiration. However, can we definitively state that aspiration occurred because our patient coughed after the swallow of a specific food or liquid consistency? In his study, titled “Aspiration risk after acute stroke: comparison of clinical examination and fiberoptic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing” Dr. Steven B. Leder determined a false positive rate of 70% and a false negative rate of 14% during the bedside dysphagia evaluation. In other words, 70% of patients who underwent an informal bedside assessment were judged to present with signs/symptoms of aspiration when an objective assessment revealed that there were none. Conversely, 14% of patients who were at risk of aspiration were missed. It can then be surmised that 70% of patients who were assessed by a bedside dysphagia evaluation were at risk of being placed on restrictive diets unnecessarily, thus, reducing their quality of life and increasing their risk of dehydration and malnutrition. More detrimentally, we can surmise that 14% of patients were at risk of being allowed to continue to consume foods or liquids that could have been harmful to their health by placing them at significant risk of developing pneumonia. The authors concluded that “careful consideration of the above issues leads us to believe that a reliable, timely, and cost-effective instrumental swallow evaluation remains the most appropriate technique to determine aspiration risk following acute stroke.”

There have been protocols created that show strong sensitivity in diagnosing aspiration risk with thin liquids, namely the Yale Swallow Protocol. However, even when the diagnostic criteria during administration of this protocol are met, therefore indicating that the patient has a risk of aspiration, an instrumental swallow evaluation continues to be recommended to determine the safest and least restrictive diet.

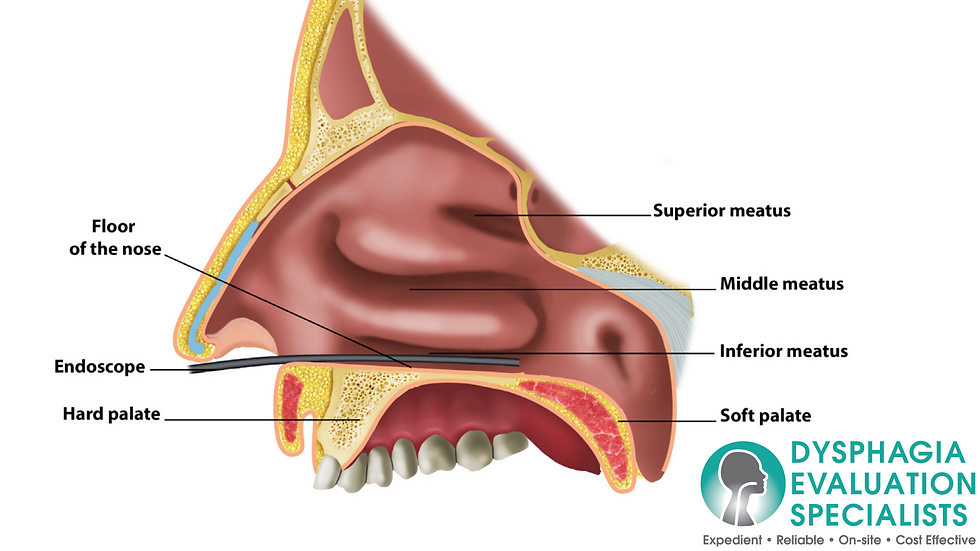

Just as phrenology has fallen by the wayside, we hope to encourage Speech Pathologists and other medical personnel responsible for the treatment and care of patients with dysphagia to delve beneath the surface of what is visible and palpable. Instrumentation such as the Fiberoptic Endoscopic Evaluation of Swallowing (FEES), can help us determine the pathophysiology leading to our patients’ pharyngeal dysphagia and tailor their treatment plan for optimal results.

Comments